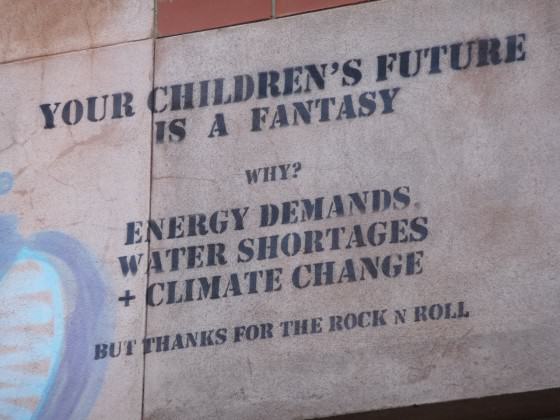

The nature of cities is inextricably tied to the nature of public space and this blog is about just a small part of that ‘nature’. It was inspired by what appeared to be graffiti on a public footpath that runs along the street where I live, in sunny Semaphore, South Australia.

Now I appreciate intelligent, well-executed graffiti. I like the stuff that possesses some style and carries a positive, or simply necessary message. The best graffiti rescues blighted spaces from greyness and orthographic rigour with dynamic swathes and patterns of colour that maybe should have been there in the first place, and graffiti has a proud place in the annals of urban ecology. Some nature-oriented graffiti in Cape Town was discussed in this blog space by Pippin Anderson.

In the late 1980s, activists from the Urban Ecology group in Berkeley used graffiti to draw attention to the collectively forgotten creeks of the city that had been turned into stormwater drains. Ecocity pioneer Richard Register made stencils and got a crew together of some three dozen people and identified nearly nine hundred places where the creeks of Berkeley went under curbs. There were twelve different stencils for all the named creeks in Berkeley, including branches of one of the five full creek watersheds. An Urban Ecology board member working for the county led to the idea being picked up as a “don’t dump, drains to bay” campaign by the counties of Berkeley and Oakland with a standardized stencil image and billboard campaign. Urban Ecology’s original campaign contributed to realisation of the restoration of Berkeley’s Strawberry Creek. During the First International Ecocity Conference convened by Urban Ecology in Berkeley in 1990, banners with the ‘creek critter’ designs flew over downtown streets. (Personal communication 8 March 2014)

Register’s original ‘creek critter’ stencilled graffiti was permitted by the city council, and thus was a meme released for stencilling and painting graffiti around street drain inlets that has since become a respectable way to celebrate a vital part of urban nature.

In California, a bunch of activists defaced public footpaths with neat paint work in order to present messages about the nature of their city and it made a positive difference that helped real change take place in the Berkeley environment. ‘Visual pollution’ became respectable in the process and stencilled and graffitied creek markers are now recognised as street art and sanctified by city authorities, as august as the state of Pennsylvania, but graffiti possesses its own kind of authority, and even when it has been assimilated by the mainstream, as happened with the street art of Peter Drew in Adelaide, South Australia, where his guerrilla poster campaign portraying historical figures in Adelaide’s downtown led to council endorsement.

Despite this kind of assimilation Drew is certain that street art will maintain its authenticity as a political statement “because there’s always going to be an illegal aspect to it…It’s a conflict between two great principles of western democracy — the sanctity of private property and freedom of expression. Those two principles clash in street art, and they will always be at odds in some way.” Peter Drew advocates street art as an unmediated medium for dissent; adamant that it needs to be treated as a legitimate form of expression, not as a problem. According to Drew, the street art graffiti community are respectful of each other’s work and of personal property — they graffiti decaying old buildings and rail yards, not garage doors on private property.

But “Late capitalism absorbs all forms of resistance and dissent.” (Sebastian Moody, ‘The Hand that Feeds — Graffiti and authenticity in contemporary brand culture’, Artlink vol 34 #1 Adelaide 2014) and graffiti is now a marketing tool, though it may be just as illegal as the tags of dispossessed youth. The stencilled graffiti that promised to let me “know the truth about Semaphore” turned out to be advertising for the real estate department of a major bank. Just another example of the 1% toying with novelty, sucking up and massaging ‘street cred’ from the language and media of the dispossessed and creating, as a consequence, visual pollution in publicly owned space.

The public realm is supposed to be something separate from the commercial realm — unless you buy the argument that nothing should be exempt from being measured and traded by commerce. Buy the argument? Isn’t that what commercial interests do — purchasing the best lines and pithiest sound bites to convince us of whatever it is they wish us to be convinced of? Done by government it’s called propaganda; done through commerce it’s simply advertising. Either way it’s about getting in the way of the eyes and minds of our daily lives. The traditional view and understanding of art is as “an authentic and sublime antidote to the overbearing rationality of commerce”. There are cultural critics who protest that ‘authentic identity’ should not be thought of and defined by its non-commercial nature. They suggest that history shows that continuing to do so is a fallacious ‘binary’ proposition in which individuals ‘continue to invest in the notion that authentic spaces’ of the self, creativity and spirituality exist as a kind of opposition to mercantile culture — if it makes money it can’t be real art. In the same way one could argue for the idea that public space is only ‘real’ public space if it isn’t part of mercantile space.

It boils down to the issue of ownership and control. In a shopping mall all activity is mediated by mercantile interests and entry is controlled so that there is no ’social’ activity outside of retail hours. In a ‘model’ traditional street, mercantile interests are clearly important, but any number of social activities and interaction can take place in the street at any time without being mediated by commercial transaction. It is in the nature of cities that they require other kinds of public space in addition to streets, and it is increasingly the case that that space must embrace living systems and support non-human species.

But what if living systems and non-human species were themselves conscripted into the armies of the advertisers?

Conscripting selfish genes

Humans are alarmingly attracted to novelty. If you think visual pollution is already a problem, consider a future in which every item and organism in the public environment is considered fair game as a potential billboard. Not content with ordinary trees and for some reason perturbed by the ordinariness of street lights, there are clever people actively working to breed trees and flowers that glow in the dark. According to the report in the New York Times, one organisation “has already obtained a letter from the department saying that it will not need approval to release its glowing plants because they are not plant pests, and are not made using plant pests.”

Whether or not to allow genetically-modified glowing trees to dominate public space by taking the place of street lights is not only a question about the ethics of genetics, it’s about the purpose and meaning of public space.

What is ‘real’ public space all about? What is its meaning or purpose? Does it need to be differentiated from privately owned space? It’s generally taken for granted by the general public and ostensibly, it’s inviolable. But in reality it’s a bit like the idea of ‘freedom’ — it means different things to different people, is interpreted differently by different cultures, and is most noticeable when it’s absent. Historically, public space has been that place, or places, where the community can gather to dance, sing, march or stroll along together, where major events in the life of a community can be celebrated or debated — in public.

Great public space is where people can escape from the boxes and buildings that mostly contain their lives and risk collective and individual dissent, face to face with others, in real space and time. It can be in the form of grand spaces, modest parks and gardens, or the footways of daily loitering and travel. But it is expressly not a corporate or privately owned domain. Owned by everyone and nobody in particular, public space offers the kind of socially mediated freedom that helps citizens work through their differences and define their commonalities. It can provide the fulcrum for social revolution or the anvil of repression. It is fundamentally about shared ownership and consequently has always been under threat from market forces.

Permanently ephemeral

All manufacturers, retailers and other businesses are as ephemeral as their products. Within a few short years, or even months, the information they contain and impart is redundant. Would a wise society embed that ephemera in the DNA of living organisms? We’re beginning to refine the idea that our cities need to be connected with the cycles of nature and that living systems are fundamental to the health of urban systems, but does glowing vegetation have a legitimate or defensible part of that vision? Historically, the great innovation represented by the provision of living nature as public open space was that it provided a place of rest, recuperation and recreation. We attribute or find meaning embedded in the natural world, as we do in human constructed space, and our urban constructs meld them into this thing we call civilisation; do we really want the nature in our cities to be represented by massively manipulated environments? Is the future now doomed to be irredeemably synthetic? Letting every pretty idea loose might have some merit, but I think it also compares with letting small kids have their way with crayons and markers in the living room.

But compare streets with shopping malls — where the only messages allowed are for commercial purposes, approved by commercial interests, solely for the purpose of selling something. Shopping malls demonstrate how the commodification of daily life looks and feels. And you can only enter between certain fixed times. This is public space in a sharply abbreviated form. It exists only at the behest or indulgence of private owners. It is not owned or controlled by the public, it is place where the public are allowed only for the purpose of fulfilling their obligations as consumers. Buy nothing, and you are barely tolerated. A shopping mall is not the public space that enables towns and cities to work. If there are no aspirations beyond those that are commodified and commercialised, then there can be no true civics.

Public space should have a timeless sense. It should be that part of the urban environment which provides the spatial armature for the rest of the city or town. Streets need to be part of their neighbourhood in a way that is, in a sense, non-partisan, a place that is not taking sides in commercial slanging matches nor telling me to be, do, say or buy anything. The street is a place where I want to be a citizen, free to use commercial services as a consumer if I wish, but not be defined by them, or made to feel unwelcome if I’m not responding to mercantile interests as I stroll along.

I, for one, don’t have any desire to walk into the public realm and be treated to yet more itsy-bitsy pieces of commercial spin.

All change

Change is normal, but change is no longer creeping, it’s galloping. Accelerated anthropogenic climate change changes the weather and landscape so that what is now ‘normal’ isn’t what was normal less than a generation ago. Everything seems to have a shifting baseline, even in the realms that used to appear stable. The children and grandchildren of people in my generation are living with a suite of ‘normal’ behaviours that were almost unthinkable when we were their age. The context of their communication is different. They are beginning to speak the language of consumers almost exclusively, a language in which everything is a product, where there are no commons and the role of civics has already atrophied into irrelevance. They are mostly passive spectators in the society of the spectacle. If they grow up thinking it’s normal to have commercial interests invading every space, can we really hope to ever again have a sane discussion about shared, common, public space?

There is one massive public space, or series of public spaces, where it is has become normal to be assaulted by histrionic commercial pleading at every turn. It’s called the internet, and it is changing our perceptions and expectations of the world at a rate that no-one really anticipated. Both the internet and public street provide a commons where people can be exposed to art and new ideas. Much more so than on the street, in this new public realm spectators can readily turn into players, seeking applause by advertising their private lives on Facebook and uploading personal movies on YouTube. Perhaps more than the street, the internet provides public domains of open access and experimentation where ideas adaptively and rapidly reproduce with what Drew calls ‘virality’ and memes spread with ease — whether or not they’re about authentic reality.

So when I stumble across a stencilled graffiti on a public footpath telling me that the truth lies in a website, and yet I know it’s not true, I’m really experiencing a kind of spam in the physical world to match what’s on-line. It’s a kind of meeting of realms where the boundaries of public and private domains are deliberately obscured and the key questions are no longer about meaning or purpose, but about who’s paying and who’s making money out of it. It’s a place in which it seems to be harder than ever to be sure what it means to be ‘authentic’ or know when the truth lies.

Afterword

I contacted my local council about the “know the truth” graffiti and they immediately sent out a graffiti-removal crew. And the council followed up my enquiry about the legality of the bank’s graffiti. I was told that the council never gives approval to activities that deface its assets. I have to conclude that the bank’s defacement of my local piece of public realm was neither legal nor was it permitted by the publicly owned-entity representing the citizens’ interest. It didn’t stop them though, and in that lovely ironic way capitalism works, this blog is itself infected by the ‘virality’ of their illegal stencils and has become an adjunct to their advertising campaign. Where does their truth lie? Everywhere!

Paul Downton

Adelaide

Good work, Paul. I was wondering about the sign myself, hoping it was something radical. (One of those stencils is one street away from us.)