A review of “A Local Neighborhood Traveler,” an exhibition of painting and drawing by Korean artist Se Hee Kim at the Boroomsan Museum of Art in Gimpo, South Korea.

On the outskirts of Seoul, tucked away into a traditional hillside garden is the Boroomsan Museum of Art. The museum sits on the edge of an enormous expanse of dry, dusty terrain. From the museum’s hillside vantage point, one can see dozens of trucks traversing the landscape in a two-file line, one in, one out. They carry away loads of soil. A few months later, a similar cadre of trucks will be pouring the foundations for what is to be another of South Korea’s ubiquitous “new town” developments.

Kim is thoroughly interested in co-discovering the relationships between people and their environments. She remains curious, not in the object of curiosity, but in the action of being curious.

Less than a year ago, this landscape was not they dusty, desolate, and Martian place it is today. It was an entire village, home to thousands of residents, small farms, schools, local shops, and marketplaces, and a small forested hill affectionately called Boroomsan (Full Moon Hill) by the villagers. It is after this hill that the museum was named.

The hill was bulldozed a few months ago, along with the rest of the village.

Looking at the landscape today, it’s almost unimaginable the swift pace and force with which the developer removed an entire town, hill, forest, and farms from the Earth. For most Korean people however, it’s just an everyday reality. The call to “modernize” the country has been going on for some decades now, and is still largely seen as a badge of pride by most elders.

Some members of the younger generation however—born from the 1980s onward, in the midst of a dynamic and active democracy—see things a bit differently. This, by way of lengthy introduction, is where we meet the work of South Korean artist, Se Hee Kim.

Inside the museum, we encounter Kim and her exhibition, A Local Neighborhood Traveler. At first glance the works, primarily small paintings and illustrations, are of ordinary scenes from life during her travels. Three distinct collections hang on the walls of the museum, comprising works created during stays in Japan and Taiwan, as well as Anyang, the town where her studio was located in Korea.

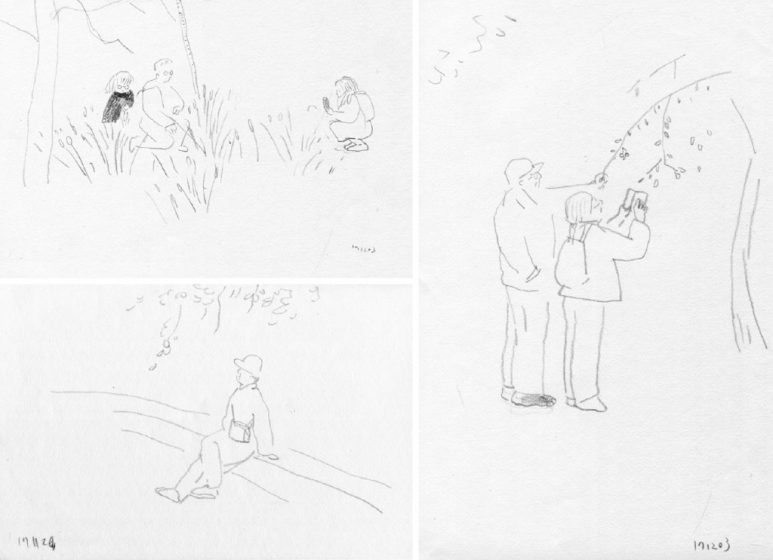

The most simple of these works are a series of pencil drawings; small scenes of individuals living and being within urban nature. Kim uses her graphite sparsely and suggestively. Figures are unmoored; people float in space together, sometimes comically, with the natural elements. The works convey comfort, curiosity, and playfulness. In these simple works, Kim seems thoroughly interested in co-discovering the relationships between people and their environments; she remains curious, not in the objects being contemplated, but in the action of being curious.

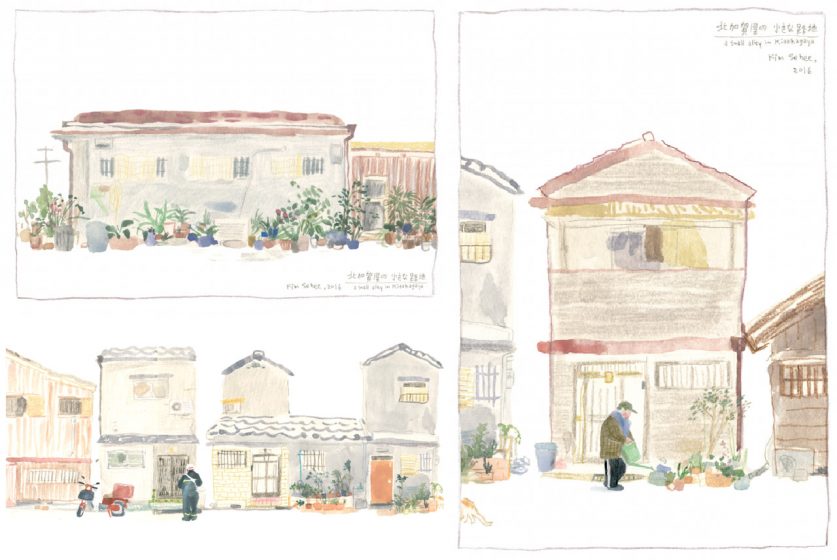

These small works are juxtaposed against a set of large-scale architectural panoramas, made while Kim was resident in Japan. The content of these larger works is broad, covering entire blocks of homes, complete with tiny urban gardens and their caretakers, parking lots, construction zones, and mailmen. These are quiet, contemplative moments, in urban nature. They take place in old, sometimes slightly crumbling towns, filled with character, with subtle diversity, with a feeling that these are spaces truly “lived” in the fullest and deepest meaning of the term.

Kim’s form and color is whimsical to an extent, yet the making of these observations of place is not an unconcerned process. Even the smallest of works, sparse as they often are, feel as if an entire day could be wrapped up into one scene. You will not sense it in a busy onslaught of figures or activities, but instead in the attentiveness and intention that is conveyed in each work.

The work here at times brings with it a melancholic impression. Is it pure romanticism? Or, is there somewhere—wrapped up in Kim’s attentiveness to the slow, the old, the diverse-yet-grumose urban worlds we are fast destroying—a reminder of something missing in our own lives?

Whichever view you take, Kim’s illustrations do provide a stunning antithesis to what is happening just outside the museum—and in so many of our own backyards around the industrialized world.

The work on display here feels in search, not only of the nostalgic and simple, but of ways to build an authentic, creative, and meaningful culture and place within an economic atmosphere that is largely unsupportive of such notions.

In light of Korea’s ongoing pace and methods of development, one hopes that delicate and emotive works such as Kim’s might help us to re-appreciate the old, the diverse, the nature-connected urban landscapes; to trust our own curiosity, playfulness, and love for the places in which we live.

Patrick M. Lydon

Osaka

Love your stories…

Love and miss you and Suhee..

Janine.