About David Maddox

David Maddox is committed to the creation of sustainable, resilient, livable, and just cities. After a PhD in ecology and statistics at Cornell he spent 10 years with The Nature Conservancy working on climate change and stewardship. In 2012, David founded The Nature of Cities and remains its Executive Director. TNOC is a transdisciplinary essay and discussion site—with 700+ writers from around the world, from scientists to activists, designers to artists—on cities as ecosystems of people, nature, and infrastructure. He is also a composer, playwright, and theatre artist. He lives in New York City.

- Web |

- More Posts (1)

Introduction

Graffiti and street art can be controversial. But it can also be a medium for voices of social change, protest, or expressions of community desire. What, how, and where are examples of graffiti as a positive force in communities?

In many cities, graffiti is associated with decay, with communities out of control, and so it is outlawed. In some cities, it is legal, within limits, and valued as a form of social expression. “Street art”, graffiti’s more formal cousin, which is often commissioned and sanctioned, has a firmer place in communities, but can still be an important form of “outsider” expression.

Interest in these art forms as social expression is broad, and the work itself takes many shapes—from simple tags of identity, to scrawled expressions of protest and politics, to complex and beautiful scenes that virtually everyone would say are “art”, despite their sometimes rough locations. What are examples of graffiti as beneficial influences in communities, as propellants of expression and dialog? Where are they? How can they be nurtured? Can they be nurtured without undermining their essentially outsider qualities?

This roundtable is a co-production of The Nature of Cities and the new website Arts Everywhere, where these responses are also published. Also check out The Nature of Graffiti, a gallery that illustrates some of these ideas from an environmental perspective.

About Pauline Bullen

Pauline E. Bullen, PhD, currently teaches in the Sociology and Women and Gender Development Studies Department at the Women’s University in Africa, Harare, Zimbabwe. She is a scholar and activist who began publishing her writings in community newspapers in Toronto, Canada, in an effort to bring public attention to racism in the schools and its effects on Black students, female and male. A lover of literature and Art, Pauline finds ways to incorporate these into even those writings deemed to be “academic”. Her most recent work is aimed at increasing awareness of the need to address violence against girls and women in meaningful and permanent ways. Hip hop and graffiti are aspects of youth culture that Pauline finds expressive.

Pauline Bullen

In Zimbabwe, graffiti images often appear in stark contrast to abject poverty or gross excess and may surface unexpectedly on the side of government buildings; on university campuses; and on walls along parks, highways, dilapidated houses, or dead-end streets. The more entrepreneurial may put graffiti images on clothing, bags, and decorative boxes that speak to an alternative and uniquely creative youth culture. For many who want to surround themselves with art that makes them feel good, the work of the graffiti artist may be too bold or too provocative. The work may also be seen as too stark, too crude, and unfinished in its attempt to bridge the gap between that which may be viewed as “less than” and the broader society; yet, it is precisely these elements that make the work dynamic and “real”.

“The moral imagination and critical capacity of Zimbabwean graffiti artists challenges a market-driven docility.”

Zimbabwe’s history of colonization informs what appears on the walls ‘tagged’ by young artists. The remains of early humans, dating back 500,000 years, have been discovered in present-day Zimbabwe and it has been possible to speculate about these people’s everyday lives and traditions from their hieroglyphic “tags” on walls in and on the outside of caves in various parts of the countryside. These early “stencil” drawings provide some insight into the lives of the people who lived outside the city and those who dominated the pre-colonial countryside—the Bantu, Shona, Nguni, Zulu, and Ndebele. Today, in a somewhat more “integrated” manner, Zimbabwean graffiti artists portray the oppressive conditions in the concrete jungle of high density areas, the conspicuous consumption and opulence of the more affluent sectors of Zimbabwean society, which is segregated still according to colour and class, though less overtly and with less of the racist economic divide that ruled Rhodesia.

Unemployed and sporadically employed “youth” in their teens and thirties may find inspiration in a spray can, a wall on a deserted street, a few yards of material, an empty carton transformed into a curio box, a bag, or even a pair of old shoes. The surface potential appears vast, particularly since the tools required for the craft are more accessible and cheaper than those needed for charcoal drawings or works produced on canvas. Sanctions imposed on the country have made many of the tools needed for other art forms luxury items that few could procure or afford. However, erasers, markers—especially concentrated but fluid watercolours to fill backgrounds and letters—are more accessible and easy to use on cheap canvases such as city walls.

Inks, inexpensive household paint, paint brushes, paper towels, makeup sponges, pieces of fabric, fingers—all are great blending tools that may be used to create larger-than-life tags, bubble letters, arrows, crowns, 3-D shapes in black and white and full color, exclamation marks, boldly defined lines, and various other symbols of an enlarged, politicized, moral imagination and critical capacity. This moral imagination and critical capacity challenges what may be viewed as a technically trained, warped, market-determined political agenda that feeds a market-driven docility.

There is a certain sense of ownership and belonging that may be gained from being able to place one’s ‘tag’, unsolicited or solicited, on a wall or on personal items in ways that force others to acknowledge and recognize your existence. There may even be a greater sense of satisfaction in having ones graffiti viewed as an authentic art form through which it is possible to gain economic independence and “legitimacy”—an art form that allows for the demonstration of a unique sensibility and, according to one Zimbabwean artist who embraces the Jamaican Rastafari religion and language, an “overstanding” of their cultural reality. However, as a rebellious act, a tool of resistance, and ammunition against corporate greed and political perversion, economic gain through independence and freedom of expression remains difficult for the graffiti artist to attain.

About Paul Downton

Founding convener of Urban Ecology Australia and a recognised ‘ecocity pioneer’, Paul was co-convener, with Chérie Hoyle, of ‘EcoCity 2, the Second International EcoCity Conference’ held in Adelaide, Australia in April 1992. His current biophilic ecocitologizing is directed through the nascent vehicle of the Ecocity Design Institute. Formed with Sharon Ede and Chérie Hoyle, EDI aims to get on-line courses on ‘making ecocities’ running during 2017.

- Web |

- More Posts (1)

Paul Downton

From here to eternity, or from free to commodity?

Graffiti is ephemeral, but can resonate long after being cleaned from the streets.

“Graffiti that is sanctioned by authority loses its outlaw power to disturb and challenge.”

At the celebrations for the new millennium, Sydney Harbour Bridge was lit up with the word “Eternity”—all because of graffiti chalked in yellow on the streets of Sydney by one lone graffitist. Starting in 1932, by 1967 Arthur Stace had chalked out his one-word message half a million times and entered the realm of legend. “Eternity” was here to stay.

“Worthless” graffiti can become a commodity, its value transformed by a simple shift in view.

Graffiti highlights one of society’s contradictions when protest is transmuted into product and neutered. Che Guevara tee-shirts, anyone? Capitalism’s ability to assimilate ideas that threaten it is unsurpassed. “Buying off” trouble is less disruptive than opposing it. Graffiti that is sanctioned by authority loses its outlaw power to disturb and challenge. When a city provides graffiti walls for its citizens, isn’t it simply extending its hegemony?

When I found stencilled graffiti in my neighbourhood and discovered that it was disguised corporate advertising, I dismissed it as worthless. If the same stencil had been about an idea rather than a product, I would have thought differently.

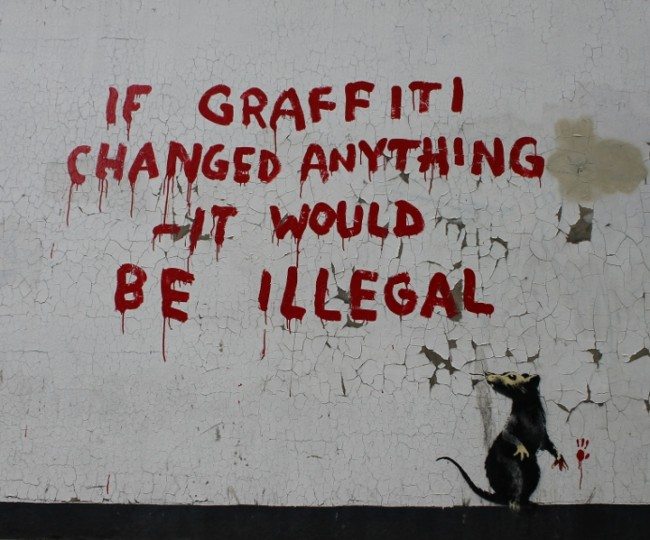

Banksy practices “protest graffiti” as high art. His work can carry multi-thousand dollar price tags. In 2007, his canvas, “Bombing Middle England”, fetched £102,000 at Sotheby’s. He trades on his anonymity and notoriety, and the commodification of his work, even its placement in galleries, legitimises it within the society that he is criticising—but as provocation or product, it’s hard to gainsay its power.

Graffitist Peter Drew is certain that street art will maintain its authenticity “because there’s always going to be an illegal aspect to it…It’s a conflict between two great principles of Western democracy—the sanctity of private property and freedom of expression”. But these principles are not universal.

In the street, claims Drew, art acquires “an anti-institutional sense”. But institutions also love it, and Drew, like Banksy, has been exhibited in galleries.

Street art that is sanctioned as a way to ameliorate dull façades is effectively assimilated as city property; it can no longer be about the conflict of ownership. It may critique the city’s aesthetics, but the city becomes as much the critic as the artist. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’s about moving on, changing the guard.

Adelaide’s previous Lord Mayor, Stephen Yarwood, saw street art as a game-changer for the 21st century city, consigning blank walls to the past. He assisted approvals and helped legalise the work of Drew and others, saying “Art isn’t just for art galleries… Cities are the best art galleries you could possibly have”.

But when the system tries these sorts of changes, the momentum of the past crashes into the present. When six street artists legitimately painted large murals on the sidewalk of Adelaide’s busiest cultural hotspots “after months of negotiations, application forms and a day’s painting, the artists had their murals destroyed less than 12 hours after they were completed by the same council that had approved and paid for them. Why? Because the council simply failed to tell the workers who clean the streets that the murals weren’t graffiti”.

There was no such confusion in 1968, when the poetry of “Sous les pavés, la plage” exhorted the citizens of Paris to embrace revolution…

And in the Paris of 2016, the unsolicited application of paint has new ways to extend its reach.

Emilio Fantin

I am interested in the ambiguity of the concept of property. “Street-writers” or graffiti artists seem to want to abolish the idea of property (symbolized by buildings) by using buildings as tools of expression. The struggle against the principle of property is directly associated with the expression of freedom, especially for those graffiti works or phrases that denounce abuses of power and discrimination.

“I thought that this art—graffiti art—could be considered as a form of collective expression, a form of meta-art.”

However, we should make a distinction between graffiti works that have political, philosophical, and poetical meanings and those which are themselves quite simply the manifestation of an abuse of power. Frustration and alienation can be transformed into an instrument of social and political demands or into aggressiveness for its own sake. The latter is a paradoxical form of property, through which abuse of free will can harm others—not only the owner of the building, but the entire community, because something coercive and ugly becomes a part of the landscape and compromises aesthetic sense.

However, we ask: Who decides on the true and right aesthetic sense? In order to judge this, I believe, one must consider the ethical principle, Aesthetics↔Ethics. In other words, quoting Heraclitus: Invisible Harmony is Better Than Visible. This “harmony” comes from understanding and accepting both forms of love: young people claim their need of truth through their aesthetic expressions, adults care about urban qualities which nourish communities’ ritual forms (or, more rarely, vice versa).

I investigated these and other topics by practicing the technique of “Strappo”. “Strappo” is a fresco restoration technique consisting of gluing canvas to the surface of the fresco and then, by pulling, removing a thin layer of the plaster with the image. It is a restoration technique adopted to save frescoes from deterioration due to mildew and water infiltrations into the wall. Years ago, I learned how to perform “Strappo”, using the technique not for fresco restoration, but for my own artistic work. At that time, graffiti and street-art were quite different from today. Sentences or phrases on the walls focused on local political problems rather than great universal issues, such as the environment, nature, pollution, or immigration. Street writers were still far away from the idea of “tags”, and the street art community was at its very beginning. Their desire to claim a space for expression within an urban context was compelling, but their gathering through an esoteric language came later.

At the end of the 1980s, I travelled in Italy and around Europe looking for walls. During my trips, I found sentences about politics, love, and sport, small colored drawings and political symbols. I collected many examples of “mural art expressions” from public and private walls, including the Berlin Wall, the University of Bologna, refuges or mountain lodges, and abandoned buildings. I thought that this art could be considered as a form of collective expression, a form of meta-art. The aesthetic is determined not only by the people who produce the work (who are, by the way, anonymous), but also by other causes (even atmospheric), time, and chance. As an artist, I need to highlight this aspect and show how meaningful collective thinking and the idea of a meta-aesthetics can be.

There are various aspects that we might tackle by talking about “Strappo” work in the urban context. If it is true that one appropriates something that somebody else made, it is also true that one preserves something that sooner or later will be erased—not one of those painted walls from which I made a small “strappo” still exists. Of course, we can photograph and document various forms of artistic mural expressions, but the fact of presenting a portion of wall in its material consistency was a provocation made in order to debate the principles of individual creation, property, collective practices, and social thinking.

I published some pictures of “Strappo” on The Nature of Graffiti.

Ganzeer

I saw firsthand in Egypt how street-art played a direct role in some of the political changes between the years of 2011-2013. There was street-art that criticized Egypt’s military apparatus so poignantly that people went out and actively chanted against the head of Egypt’s Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. This was simply unheard of. I also saw a wall of murals commemorating fallen protesters turn into a shrine, where people would come place flowers and look at portraits of their friends and loved ones. I saw murals that were even the cause of huge clashes. Egyptian artists really knew how to utilize the power of street-art, which is precisely why the Egyptian government introduced and heavily enforced anti-vandalism laws akin to the ones established in America.

“If unsupervised spaces were widely available—even in Western countries—some very beautiful and socially conscious artwork would emerge out of them.”

Street-art festivals, the method through which cities offer a legal venue for artistic expression are great, but I find that they seldom result in genuine social expression rather than works that are, for the most part, decorative. There are a few exceptions to the rule, such as the works of Blu, and recently Herakut, and sometimes Os Gemeos, but for the most part, artists tend to treat these festivals as an opportunity to showcase their signature styles or to try out new techniques rather than an opportunity to say something relevant.

While I wouldn’t necessarily blame this on the festivals themselves, and it has a lot more to do with the individual artists involved, the truth is that organizers of these sort of festivals are primarily interested in a particular street-art culture that celebrates style more than anything else. Uncurated and unsupervised spaces of visual expression are vital for the emergence of socially conscious artwork outside of the rather closed off subculture of street-art.

Graffiti as a symptom or cause of urban decay is a very Western phenomenon due to the art form’s early associations with gang culture. For the rest of the world—which is actually the vast majority—both graffiti and street-art tend to be utilized as modes of social expression. Seldom will you find practitioners obsessed with their tags or with drawing cool looking images that don’t necessarily mean anything. As opposed to what is common in the U.S., a person’s drive to go and write or draw something on a wall has very little to do with ego or self gain, and far more to do with the need to go out and express a social concern or a political criticism. Of course, this does not take away from the controversy associated with graffiti and street-art, but adds to it.

Having said that, I still think that if unsupervised spaces were widely available—even in Western countries—some very beautiful and socially conscious artwork would emerge out of them. It would, without a doubt, start off with haphazardly done tags and whatnot, but I imagine it would slowly evolve over time. Someone would come and write something, then someone else would come and draw something in response to that, and then perhaps someone would come and build on top of that drawing, and so on. Rather than a sacred piece of artwork, framed and hung inside a museum upon completion, this would be an ever-evolving kind of street-art. Very alive and always changing as per the whims and conditions of its surrounding inhabitants. Artwork that is as much alive as the cities that host them. That’s the kind of street-art I’m really looking forward to seeing.

Germán Gómez

Graffiti—the arbitrariness of the “beautiful”

The Mayor of Bogotá, by order of a judge of the Republic of Colombia, regulated graffiti through a legal act, Decree 75, which established places where graffiti was prohibited or allowed by law. On this basis, the Mayor took actions to promote graffiti and provide the general public with information about graffiti and the decree.

“In Bogotá, graffiti—of young people following football clubs, writing of hip hop culture, art murals, political graffiti—has many stories to tell.”

In fact, the practice of graffiti in Bogotá has grown considerably, regardless of its regulation. It can be seen on the walls of houses, on the doors of commercial establishments, on the great walls of entire buildings, in parks, bus stops, on buses, and generally in almost any area of the city. Such graffiti—including street art, graffiti of young people following football clubs, writing of hip hop culture, art murals, political graffiti—has many stories to tell, including signatures or tags.

Decree 75 of 2013 regulates the legality of graffiti, regardless of its aesthetic quality, emphasizing the process that defines the permissions of the owners of the places where graffiti is made. That is, no matter how ugly or beautiful, it is critical to have the permission of the owner of the property before graffiti is created. The decree has generated some public acceptance of certain types of graffiti while others remain less popular. For example, street art and murals are “accepted” as “beautifying” the city. Other graffiti is less accepted, such as football related graffiti, political messages, and, especially, tagging. There are several surveys indicating improving public opinion of graffiti. An opinion poll, conducted by the City of Bogotá in 2014, found that only 38 percent of the population recognized the value of artistic graffiti in improving the city. But in 2015, a poll by the Bienal de Culturas found that 67 percent believed that artistic graffiti improves the city.

The patterns and their difficulty, the techniques, the explosion of colors and tones in the image, for example, are all components of graffiti writing. The way in which images and messages are drawn and encrypted are not easily understood and may transcend the general concept of “ugly”. In turn, a large and composite “image” composed of many tags—for example, Caracas Avenue, with hundreds of tags in one block—mixed with outdoor advertising, is an aesthetic delight from a contemporary perspective. Writing on the walls of the city generates phenomena of interpretation, not only in the field of semiotics, but also in simple enjoyment and aesthetic interpretation. However, some associate graffiti with perceptions of insecurity, invoking theories such as “broken windows” and justifying cleaning graffiti, which, from such perspectives, is “ugly”.

The debate is, therefore, open. Of course there are interest groups for or against graffiti in Bogotá that are associated with major economic groups. However, practitioners of graffiti are clear about something: with permission or without, graffiti will continue to exist in Bogotá.

Sidd Joag

During the late hours of November 18, 2013, property developer Jerry Wolkoff, of G&M Realty, whitewashed the Institute of Higher Burning, also known as 5Pointz, in Long Island City, Queens. This, just 3 days after a rally to protect the beloved international landmark from demolition, and mass outrage at the plan to build a condominium complex on site. A year later, all that was left in the wake of its destruction was flattened rubble, construction scaffolds, and cranes. And, a deep socio-cultural scar on residents of the city and the international graffiti community.

“Graffiti is arguably the most relevant art form of our time, yet it is attacked, destroyed, and routinely commodifed in the service of gentrification.”

For over 20 years, 5Pointz was a most powerful force of positive change in New York City, particularly for its youth. I was 15 when I first visited 5Pointz, then known as the Phun Phactory. I was a fledgling graffiti writer, only rarely mustering the courage to get up outside of my blackbook. But I was deeply infatuated with the form and determined to get better. The more I painted, the more I met other writers.

My foray into graffiti was the first time I truly felt part of a community. 5Pointz was a magnet that drew us together. Graffiti gave us a stake in our city and connected us to the world at the same time. We didn’t have to risk arrest and we could take our time, honing skills and sharing ideas. The massive structures covered in hundreds of shades and layers of paint were a revelation. The fact that nobodies like us could paint next to legends was exciting (and terrifying), and motivated us to paint harder.

It was thrilling to see your own piece from the 7 train, knowing that thousands of other people were seeing it too.

Given all of the destructive activities we’d likely have engaged in, graffiti offered a compelling alternative: creative expression and the respect that came along with doing it in style. Yet, the medium itself and those who practice it are routinely criminalized.

Graffiti is arguably the most relevant art form of our time. Yet, it is attacked and destroyed where it is most accessible and where it is most at home. At the same time, it is routinely commodifed in the service of gentrification.

In New York City, its birthplace, graffiti has been under constant attack since the late 1980s. First, as a target of quality of life policing and the “buff”, and, more recently, as a casualty of gentrification. It’s important to note that the tactic of recklessly painting over graffiti, which is generally uneven and mismatched in color, is more symbolic than practical. It sends a message to writers in general, and the young people and communities (of color) where graffiti originated—that their creative expression is not wanted, is of no value, and is therefore expendable.

Long Island City is one of the most rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods in New York City due to its proximity to Manhattan. But it is artists, like those that popularized 5Pointz, who, in part, brought the neighborhood attention and raised its value. Once they had served their purpose, they were disposed of in favor of condos for the rich.

I’ve had many arguments about this. People point to Williamsburg and Bushwick as new “meccas” for graffiti, without recognizing that in these neighborhoods, graffiti, murals and other public art have played, and continue to play, a key role in the displacement of locals, in favor of young outsiders who can afford higher rents. They, in turn, attract rich property developers, who, when they take over, will permit graffiti within certain parameters that serve their interests. Like Jerry Wolkoff, who has promised to maintain significant wall space in his new development—built over 5Pointz—for graffiti writers. How much space, exactly? Who will be allowed to paint? What will be the criteria? These are all questions that fall on deaf ears, as we are reminded that we are lucky to be getting any space at all. Fuck that.

There is no shortage of evidence that spaces like 5Pointz are invaluable safe spaces for the young people of New York City. They provide access to the arts and culture as alternatives to high-risk behaviors and delinquency. They expose our youth to the world and all the possibilities that exist within it. Yet, they are directly, or indirectly, under attack. What can we as artists, appreciators, New Yorkers, and global citizens do to fill the abysses left by the destruction of OUR venues for creative expression?

Patrick Lydon

Looking from behind the stacks of legal cases brought against graffiti artists over the past several decades, it’s easy to see these individuals as graffiti “vandals”. On the other hand, walk into any of the number of tragically hip galleries and museums who showcase graffiti artists today, and these individuals are posed as “visionaries”, instead.

“There isn’t such a wide divide between the actions and intents of the graffiti “artist” and those of the graffiti “vandal”.”

From this mindset, we arrive at what are two dominant “conventional” views of graffiti:

1) The graffiti “artist” is a sanctioned professional who creates socially challenging work that museums and patrons spend money to buy and support. Seen as a “productive” use of capital, we judge graffiti artists as beneficial.

2) The graffiti “vandal” creates socially challenging work that defaces public and private property, and which we spend public money to cover up. This being an “unproductive” use of capital, we judge graffiti vandals as burdensome.

These two popular views should tell us quite a bit about the obtuse condition of our social, legal, and economic systems, because in reality there isn’t such a wide divide between the actions and intents of the graffiti “artist” and those of the graffiti “vandal”, save for the one which these systems create.

The force that motivates many graffiti artists is, in fact, identical to that of many so-called “legitimate” artists. The major difference? The “legitimate” artists have found—or were given by status, privilege, or luck—a way to fit their work into the economic system.

This points to something most of us reading this already know well: lack of opportunity—or even perceived lack of opportunity—is a cause not only of graffiti, but of violence and crime and economic inequality. The solution, plainly put, is that our cities need more opportunities for young persons to contribute their creative hands and minds to their communities in ways that are socially productive.

City administrators tell us this is easier in theory than in practice, yet it becomes easier in practice if we let much of that theory come from the mouths of those who are primarily affected.

A few years ago, I teamed up with Mary Cheung, a photography teacher at Gunderson High School in San Jose, California. We asked a group of her students to use photography and written word to address issues that were impacting their lives. The works they handed in tackled surprisingly deep issues, from drugs to discrimination to sexual orientation.

Out of fifteen students, five wrote about graffiti.

Why not listen to the youth? Their insights are vivid…

“It is better for artists to be squeezing down on [spray] can caps than gun triggers”, was the conclusion that students Ryan Tran, Eric Gonzalez, and Adrian Morales came to.

How often does law enforcement take this view? Perhaps not often enough. One can’t help but think how many lives would be saved or changed if they did.

Two other students, Nick Melchor and Jeilah Evaristo, wrote that “…people only point out the negatives, not seeing the untapped talent the city has to offer”.

Nick and Jeilah went on to give an insight that surprised me because of how truly it rang in my mind; these two students wrote that graffiti “may be seen as a negative, but it gives off color to a plain and hurt city”.

A plain city.

A hurt city.

Two 15-year-olds see a hurt city, and they see graffiti as the color and expression, if not necessarily to show that hurt, then to provide an alternative to it. They also see, in themselves and their friends, an untapped talent; a talent with no logical outlet in their world other than on freeway overpasses and walls.

Colorful bandages applied to a hurt city. It’s not just poetic. It’s reality. It’s theory from the street.

There are few examples—Rio di Janeiro, Seoul, Bogotá, and others that will doubtless come up in this forum—where governments have realized the same reality that these two young people have.

The positive examples show governments using honesty and compassion, involving disenfranchised youth in the direction of cities and neighborhoods instead of locking them behind bars; they show neighborhoods not just coming alive with color, but disenfranchised youth coming alive to believe in themselves, to discover and use their unique skills and passions to make their corner of the world better, regardless of whether they go on to be professional artists, business leaders, local politicians, or homeless recyclable collectors.

The positive examples bring notions of community and economy closer together, instead of continuing a dangerous global trend of pushing the two farther apart. In doing so, they create viable opportunities for individuals to build and join a community-focused economy.

When governments and citizens begin to see the world from the eyes of disenfranchised graffiti artists, when our theory comes from the streets, we’ll begin to see more positive examples and indicators, and more cities where the human impulse to be creatively employed is embraced, encouraged, and championed, even if this impulse presents challenges to our status quo.

Patrice Milillo

What can it be: a critical look at the complexities of “graffiti”

As I strolled through the cobblestone streets of Prague admiring cathedrals, statues, and horse-drawn carriages that transported tourists through what resembled a renaissance painting, I felt a real sense of tranquility. However, this feeling was instantly disrupted by the sight of a van that was completely covered with spray painted scrawls. The contrast of the van against the beautiful backdrop of antique Prague was similar to a pile of burning tires in the middle of a pristine rain forest. No one could ever convince me that this is a form of art.

“Any movement a city is willing to spend $300 million to eradicate deserves careful examination.”

Is it boredom, anger, or a complete disregard for public and private property that compels a person to do this? Is it a response to certain stresses, a cry for help, an intrinsic human need to be acknowledged, or something else? Regardless of where the compulsion arises, some forms of “graffiti” are nothing more than obnoxious acts by selfish individuals who feel entitled to claim space that isn’t theirs.

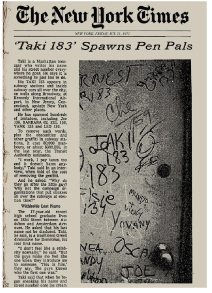

Many are confused by the term “graffiti”. It is ambiguous, confusing, and controversial because it encompasses everything from turf markings and vandalism to murals and advertising, which is why a historical account is necessary. The recognized incubation zone for what is referred to as modern “graffiti” is New York City, and it did not start as art, but tagging: scribbling one’s name in as many places as possible. On July 21,1971, the New York Times published an article titled, “‘Taki 183’ Spawns Pen Pals”, which featured a 17 year-old writer by the name of Taki 183, who literally made a name for himself by tagging his nickname across all five boroughs of New York City. To answer the question of who was behind these acts, the article quotes a New York Transit Authority patrolman, Floyd Holoway, who explained that he had “caught teen-agers from all parts of the city, all races and religions and economic classes”.

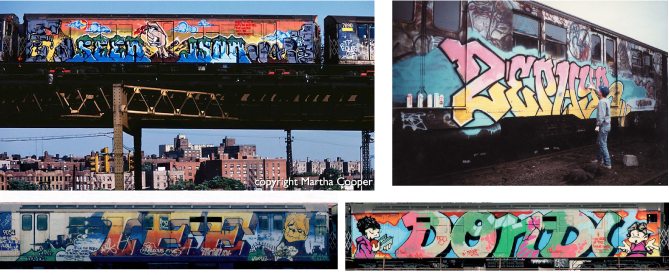

Perhaps the popularity of tagging was a response to boredom, frustration, or just the excitement of getting away with using subway cars and city walls as one’s personal billboard. Whatever it was, the article inspired multitudes to join in the competition. Though the act of scribbling one’s name on a wall may not be revolutionary, the fact that it resonated with so many and crossed racial and socioeconomic barriers was. From this starting point, participants set themselves apart by developing their monikers into increasingly sophisticated forms. This ushered in a new generation of artists like Lee Quinones, Seen, Dondi, Zephyr, and many others who painted high art on the sides of subway cars and buildings around the city.

On a recent Art is Power tour of Europe, I interviewed prominent graffiti and street artists to discuss this development. I had the honor of meeting with Mode2, a first generation European graffiti pioneer who has stayed dedicated to graffiti art and Hip Hop culture for over 30 years. In describing the ethos of “graffiti” art, Mode2 explained,

“People had to somehow be original and interpret an aspect of themselves. To be original, you have to draw from your own background, your own culture, your own personality, what you’ve lived through.”

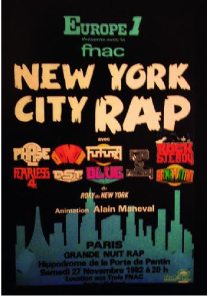

No matter where a person may be from, personal and cultural validation and the need to be acknowledged are universal human desires, and graffiti provided the framework. By 1982, when New York sent its best ambassadors of Hip Hop on a global tour called The International Hip Hop Concert Tour, “graffiti” had evolved into high art, which made it extremely appealing.

As in New York, European youth from all backgrounds had a democratic outlet that provided a sense of purpose, community, and fun. Some became artists and others scribbled their names, but for the ones who took it to the next level, “graffiti art” was empowering.

Medellín, Colombia boasts a similar story. Due to the unbridled cocaine trade of the 1990s, violence, fear, and drug addiction ravaged many communities. In the ashes of this difficult time, Henry Arteaga, a founding member of the world famous Crew Pelegrosos, 4 Elements school of Hip Hop, explained: “There were no cultural offerings, and the state left its youth abandoned.”

To make matters worse, since countless youths had been swept up by the drug cartels, there was a huge generational rift. In response, Henry and his friends took up “graffiti” and the other elements of Hip Hop. As in New York City and Berlin, youths in Medellín began interpreting aspects of themselves and their environment through “graffiti”, which empowered them to reclaim their communities. According to prominent sociologist and activist, Dr. Charles Derber:

Most social movements rely on art as a powerful vehicle for expressing dissent and resistance as well as helping articulate new visions of society.

The beautifully executed artwork adorning the walls of the Hip-hop school and the surrounding neighborhoods illustrate the power of “graffiti” to, as Dr. Derber put it, “articulate new visions of society.” “Graffiti” was an effective implement for restoring humanity in a shattered community. Arteaga enthusiastically explained that today, the older generation, who were once terrified by the youth, no longer fear them.

Such examples illustrate the role of the arts in creating opportunities in bleak circumstances. They also illuminate “graffiti’s” subversive character, since the audacious act of appropriating public space for personal expression is a form of dissent, scary to people in power. In a 2013 Lecture at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Professor Noam Chomsky (45:44) explained:

“When people in power believe something firmly, it’s worth paying attention to them. And I think they believe firmly that you should not have revolutionary popular art in which people participate. Actually, that’s one of the reasons, I think, for destroying the graffiti on the New York subways.”

Again, calling “graffiti” revolutionary may seems exaggerated; however, consider that it integrated a whole generation, taught them to, as writer and social critic Adam Mansbach states, “negotiate the urban sub-terrain of the New York subway system,” dominate public discourse, and then spread to virtually every country on the planet. It is also telling that from 1972 to 1989, New York City spent over three hundred million dollars on a “war on graffiti”. Any movement a city is willing to spend that kind of money to eradicate deserves careful examination.

In cases like New York, Medellín, and Berlin, individuals have employed the democratic, creative, and subversive attributes of “graffiti” to re-imagine, redefine, and recreate their realities. In other cases, individuals feed their egos by selfishly tagging their names on any surface that catches their attention. This clearly illustrates that “graffiti”, like any powerful medium, can be constructive or destructive depending on the individual doing it. Glorifying or demonizing “graffiti” is a simplification that diminishes its complexity.

Laura Shillington

Graffiti, space, and gender

Graffiti art disrupts urban space in multiple ways. It interrupts the seemingly planned nature of cities, in particular in the hyper-planned city spaces of the global north. But the act of producing graffiti also interrupts normative ways of being and living in the city. To create graffiti is to do something illegal (in some cities), out of the ordinary, and in the margins of the city. Graffiti can be used to mark territory—as is the case with gangs in Los Angeles or Rio de Janeiro. It is can be used as a ‘public’ voice of marginalised populations. However, in many cities across the globe, graffiti is produced predominantly by men. In this sense, graffiti—both the art and act—are generally perceived as masculine. Why?

To create graffiti requires placing one’s body in risky places at precarious hours (e.g. at night). Women in most cities are still far more vulnerable that men, especially in certain places and at night. Women graffiti artists experience street harassment by men, including sexual harassment by police officers. Indeed, the women that create graffiti face more challenging situations, making their graffiti more significant to urban spaces. Moreover, the images and texts that many of these female artists create have an important social message. Putting themselves at risk to produce art (much of it political) is a claim to the right to the city: a demand to be safe and to be able to engage in producing urban space.

Yet, there are many great female graffiti artists, and the number is growing. In 2010, several women from Nicaragua and Costa Rica formed to create Las Destructoras (or Ladies Destroying Crew). These grafiteras have painted graffiti in Managua, San José, and several other cities. Most of their work has comprised tagging words, such as mujeres libres, fuertes, bellas (free, strong, beautiful women) and female figures, along with their tag names. For women, making graffiti—being in public (usually in groups)—is a rebellious act that disrupts the usual perception of young men transforming city spaces. It provides a sense of power over the city, their bodies, and the public (in relaying messages). In Nicaragua, the group has given workshops on graffiti to women in Managua and other cities.

That grafitti art in many cities is dominated by men means that even within marginalised (non-formal) productions of urban space, women’s art and voices remain side-lined and out of the public view. In this regard, the growing number of women graffiti artists is a positive force within communities. These women are helping make urban space (especially public and street spaces) safer by making their own presence visible—not only by puttng their bodies physically in these spaces when they create the art, but also through the female images and messages they leave behind. Such messages may help to generate discussions about street safety, harassment, and women’s roles in (public) art. Allowing young women to engage in graffiti may also help build confidence. The workshops that Ladies Destroying Crew have given on graffiti is one way to cultivate a culture of women and graffiti. Perhaps there are other ways that communities, organisations, and cities can use graffiti as a way to bring about more gender equity in urban spaces?

To meet the Ladies Destroying Crew, see their Facebook page (with an introductory video):

- https://www.facebook.com/lasdestructoras/videos/10150719603779105/?theater

- https://www.facebook.com/lasdestructoras?hc_location=ufi

Also:

- http://lasdestructoras.tumblr.com/

- https://saravannote.wordpress.com/2012/05/07/girls-graffiti-ladies-destroying-crew/

Other websites dedicated to female graffiti artists:

- http://www.womenstreetartists.com

- http://madc.tv (website of German graffiti artist Claudia Walde a.k.a. MadC)

Great article on Brazilian graffiti artist Panmela Casto:

Brown, G. (2012) Street Smarts: The Gender Justice of Graffiti Artist Panmela Castro. Bitch Magazine: Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Fall, Issue 56, p42-45.

Advertisers pay the owners of publicly visible sites. They do not pay the viewers for trespass on their vision. Bravo to graffiti artists for breaking the monopoly of money over what we see.

The monopoly of information creates distortions in public opinion makes the case is defined as graffiti vandalism . Despite its power and ability to go beyond the official discourse is something that enriches the public.

Thanks for your opinion

Graffiti is a triggered emotional response to an inner conscious or unconscious call for justice and understanding. If the spaces weren’t or aren’t made available, it would be like having denied first humans to embed petroglyphs in cave walls. Graffiti is genetic human nature.

Therefore, graffiti expression should be a right. The controversy lies in the notion of public and private. Because in ancestral times that concept did not exist, it was the community who gave birth to graffiti out of the primal need to communicate.

You are my hero today Frida. Thank you for this.

Patrick, you make some good points in your article. Graffiti wasn’t considered an art until the galleries realized that they could make money off of it. The more it becomes commodified the less democratic it becomes. Like it or not, the illegality of the act in itself is a political statement.

Bogota exists in a very strong relationship with the discussion bathroom graffiti and public space . Mass Media Economic Groups belonging to argue that it is of both ” artistic ” Mar is a contribution to the landscape of the city . the concept of “art” that is imposed from Manages Media THESE leaving out everything they considered ” vandalism ” .

Very well said, Frida!

Degenerate forms of power show up through automatisms: one does something without being aware of what he is doing. Media system power takes advantages of our lack of conscience. Many of the sentences or tags that I see around on the walls of the cities seem to be made in this way. It smells of frustration and alienation. However, frustration and alienation can be transformed in aesthetic and political tools if they are fertilized by inspiration and intuition. My invitation is to consider “graffiti e street art” as a form of expression which can have a strong political impact: do not consider walls as a personal blackboard but be conscious of our feelings, ideas and talents in terms of giving a contribution to a “conversation” (also and above all with our “enemies”)

I agree. However, we have to be careful not to universalize all graffiti as an expression of anger/frustration against hegemonic powers. In some cases, graffiti (including tagging) can reinforce hegemonic ideas. In particular patriarchy. The graffiti that is used by gangs to mark territory can be incredibly misogynistic and does not counter prevailing systems (in this case patriarchy). Thus it does not counter prevailing powers but rather supports a particular form of prevailing power.

Graffiti is a powerful tool to counteract the arbitrariness of power. The walls never stop talking …

‘The walls never stop talking’ – I like that a lot!

Tagging versus Graffiti

There is an interesting tension between what counts as graffiti and tagging. Is there a difference? Is tagging a form of graffiti? Or is it it’s own category? Indeed, those who tagg seems to fall more easily into Patrick’s category of vandal (as opposed to artist)?

Tagging versus Graffiti

There is an interesting tension between what counts as graffiti and tagging. Is there a difference? Is tagging a form of graffiti? Or is it it’s own category? Indeed, those who tag seems to fall more easily into Patrick’s category of vandal (as opposed to artist)?

Great topic, thanks for this!

Concerning the beneficial influences of graffiti, there is an interesting example in East Harlem. The Harlem Art Collective (HART) “took over” a wall on 116th street, and they use it to express and encourage art with political and social intentions. This month, for example, the wall focuses on women, women rights and gender equality, in celebration of International Women’s day. Not only they do their own “guerrilla art”, but they also encourage people in the community to share their art, poetry, photographs, or anything they want on the wall.

On their Facebook page (www.facebook.com/theHarlemArtCollective) you can see photos of the different themes they have focused on. On this page they also share their goals, among which we can highlight: “Inspire our community and encourage artistic expression; create an inclusive and welcoming environment for everyone to participate” and “Instill pride and respect in our neighborhood by beautifying and restoring abandoned and neglected spaces.”

On this regard, I have a few questions: To what extent are they accomplishing these and their other goals with their actions? What are the keys to success in the use of graffiti art as an effective tool to have a positive influence in a community? How can we measure the alleged beneficial influence of graffiti art? What is the lifespan of these benefits? Do these benefits transcend the ephemeral art that brings them about?

A good example of the positive energy that graffiti can generate, but Javier, why do we need to ‘measure’ the benefits of graffiti art? What kind of quantification do you have in mind? How on earth do you establish whether the “benefits transcend the ephemeral art”? Isn’t that a step towards entirely unnecessary commodification?

We must be able (perhaps we have to relearn) to conceive of the various strands of life, human and otherwise, without placing them in the framework of measurement and commodification or else we run the risk of never being able to see the world without burdening our vision with the myopic distorting glasses of the marketplace.

Wonderful … Only through the measurable human is built ? Although surely they will exist indicators measuring sensory experiences the subject of graffiti contribution to community building goes beyond , as Paul says , conventional measuring systems. The other week will share their experience of a woman stencil, that writer in Bogota, and how its practice contributes to building community from the sensible . And if we see the points made by Javier in relation to the Harlem experience it can be seen only with images power in terms of building (social, artistic , urban ) relationships generated .

You need to try to measure what is done , but it is more important to share when it comes to graffiti , is IMHO

On the point of “measurement” I can see both Paul Downton’s and Javier Otero’s points. I’m not sure how one would study the lasting impacts of ephemeral graffiti, as Javier suggests, but there could be some valuable ideas that emerge from studies about changing public attitudes about graffiti. Javier’s point also reinforces the idea that graffiti *has* benefits—that’s what this roundtable is partly about. It’s good to explore what these benefits are, or are not—both in scholarship and public fora—both to individuals and to communities.

And surely we should make concerted efforts to document graffiti—this is a form of measurement also. Indeed, there are many such efforts underway.

This is a very delayed response. Part of what makes graffiti powerful is lack of permanence. Society — and thus power — is never static. Graffiti can be read as a response to the changes in society, thus the importance of documenting. Graffiti is simultaneously a present and historical moment (representative of change). The Harlem Collective that Javier points to is a wonderful example.

The act of making graffiti (not just the final product) can be incredibly beneficial. It can create a sense of power — of acting against a ‘wrong’ (for lack of a better word) — of taking over space. Writing and drawing graffiti can be seen as an act of pleasure, a desire to write and express. It is seen as relaxing by some artists – a form of therapy. (There is great article on this called “‘Our desires are ungovernable” – I can pass it on for those interested).

Another sort of graffiti that we have not explored here is bathroom graffiti. Much of this is less graphic and more text. Graffiti writing on bathroom stalls — at least in the women’s stalls in my experience — can incite conversations about topics such as romance and relationships (heterosexual and homosexual), rape, empowering women, degrading women, anti-capitalism, etc. The bathroom stall becomes a space of communication, of empowerment and can be very beneficial to those who are not able to speak up in other spaces.

In Bogota the participation of graffiti artists is promoted in a space where its promotion issues will be discussed . Do you know a similar experience ?

http://www.culturarecreacionydeporte.gov.co/es/abierta-convocatoria-para-escoger-representante-del-comite-del-grafiti-en-bogota

Yes, this is very common in boroughs in Montreal. Since 1996 there has been an annual festival called “Under Pressure” which aims to create a dialogue between communities, government and artists about graffiti. Many years there is a theme, sometimes about political topics and the role of graffiti.

http://underpressure.ca/

That’s cool, but that still doesn’t fall under “unsupervised graffiti spaces.” It’s still an organized festival, where artists are chosen and the walls they paint are protected. It isn’t entirely the same thing I’m suggesting.

Thanks for that, Laura. It sounds like the graffiti in women’s bathrooms is far more interesting and meaningful than that of male bathrooms, which unfortunately still revolves around tagging and promotional stickering. Very egotistical and outright pointless stuff.

Come to think of it, I guess that shouldn’t be surprising at all.

Thanks Laura.

Art is very helpful to get the attention of the kids, most especially graffiti. However, the design for graffiti could be chosen carefully that is good for the kids.

Art is very helpful to get the attention of the kids, most especially graffiti. However, the design for graffiti could be chosen carefully that is good for the kids. Thank you for the idea.

this is a good page